A travelogue of space, history, and healing

Journeys That Are Not Planned

Lago di Como - from my personal archive

Some journeys are not chosen by the mind, nor planned by reason.

They seem to be guided by subtle laws of the spirit and by an inner rhythm that reveals itself only when we descend into personal silence and truly listen to what has always been present there. By following that rhythm, we are in fact following the path of personal maturation, knowledge, and healing. Cities, people, and landscapes thus become mirrors of inner processes, and movement itself takes the form of a quiet meditation in motion.

Mediterranean Roots: Salona and Split

This story begins in Solin, in ancient Salona - a place where the ancient world met early Christianity, and where care for the body intertwined with care for the soul. It was here that a search for meaning and for what truly heals first awakened within me.

Split, once Spalatum, became the city of my maturation: the place of schooling, medical studies, and the beginning of my professional path as a physician. A city grown out of Diocletian’s Palace , it has for centuries been exposed to successive rulers and worldviews, yet it has preserved its unique, continuous pulse of life.

Bell Tower of St. Domnius, view through the Silver Gate, Split – from my personal archive

Diocletian and Mediolanum – A City of Reforms

During the reign of Diocletian, at the end of the 3rd century AD, Milan (ancient Mediolanum) was designated one of the key administrative centers of the Western Roman Empire. As part of Diocletian’s reforms, the empire sought stability through a new territorial and administrative organization. While the emperor, at the height of institutional power in 305, withdrew to the residence he had begun building a decade earlier—out of which Split would later grow—Milan assumed the burden of governing the western part of the Empire, shaping itself into a city of order and responsibility at a time when the world in these regions was already undergoing irreversible transformation.

The North as Counterpoint: Como and Milan

Lago di Como - from my personal archive

From Mediterranean Split, in recent years my path has repeatedly led northward, to Lombardy. Lake Como feels composed and contemplative, almost monastic, while Milan is its opposite: urban, precise, full of rhythm, yet layered to such an extent that every street seems to conceal its own subterranean stratum of memory. It was precisely in this same city, in 313, shortly after the death of Emperor Diocletian, that religious tolerance was proclaimed - a sign of a profound civilizational shift in which Christianity, already woven into the lives of many communities, began a new chapter of its public and institutional presence throughout the Mediterranean and beyond.

Duomo di Milano - from my personal archive

And while in Milan Christianity was recognized and shaped within state structures, in Salona (as well as in several other powerful trans-Mediterranean early Christian communities—from Rome to Smyrna (Izmir) and Jerusalem in the East, and from Lugdunum (Lyons) in the West, as well as from Carthage in the South to Siscia (Sisak) in the North) it had already been deeply lived: in communities, in martyrdom, in the everyday lives of people who carried the new faith as a profound inner experience. The basilicas, cemeteries, and testimonies of martyrs in Salona speak of a transition between epochs that did not begin with a decree, but with a powerful inner awareness and a living vision of Christ’s life.

Top of the Bell Tower of St. Domnius, view through the Vestibule, Split – from my personal archive

Within this broader historical framework, a particular structure inside Diocletian’s Palace acquires special significance: the mausoleum that the emperor had built at the beginning of the 4th century as his future burial place. After the fall of the Roman Empire and the gradual Christianization of the city, this monumental structure underwent an extraordinary transformation—it was converted into a Christian cathedral and dedicated to Saint Domnius (Duje), the bishop of Salona and an early Christian martyr who suffered precisely during Diocletian’s persecutions of Christians. Today it is the Cathedral of Saint Domnius in Split, one of the oldest cathedrals in the world still in continuous use within its original ancient structure.

Cathedral of St. Domnius, Split – from my personal archive

Shifts of Power and the 19th Century

Both Split and Milan share a long history of changing rulers. This dynamic suddenly flashed through my mind while passing across Piazza Cinque Giornate. The square commemorates the Cinque Giornate di Milano - the five days of uprising in March 1848, when the citizens of Milan forced the Austrian army to withdraw. Freedom, however, was short-lived: already in August of the same year, the city was reoccupied by Field Marshal Josef Radetzky. Although this occupation restored Austrian control over Italian territories for several more decades, the uprising became a symbol of civic resistance and a key moment of the Risorgimento (Italian unification).

Significantly, the 19th century—an era of the breakdown of old orders and the spread of ideas of freedom—was also a time of strong flourishing of homeopathy in Europe. Medicine, in parallel with social changes, began turning toward a more humane and individualized approach to the patient.

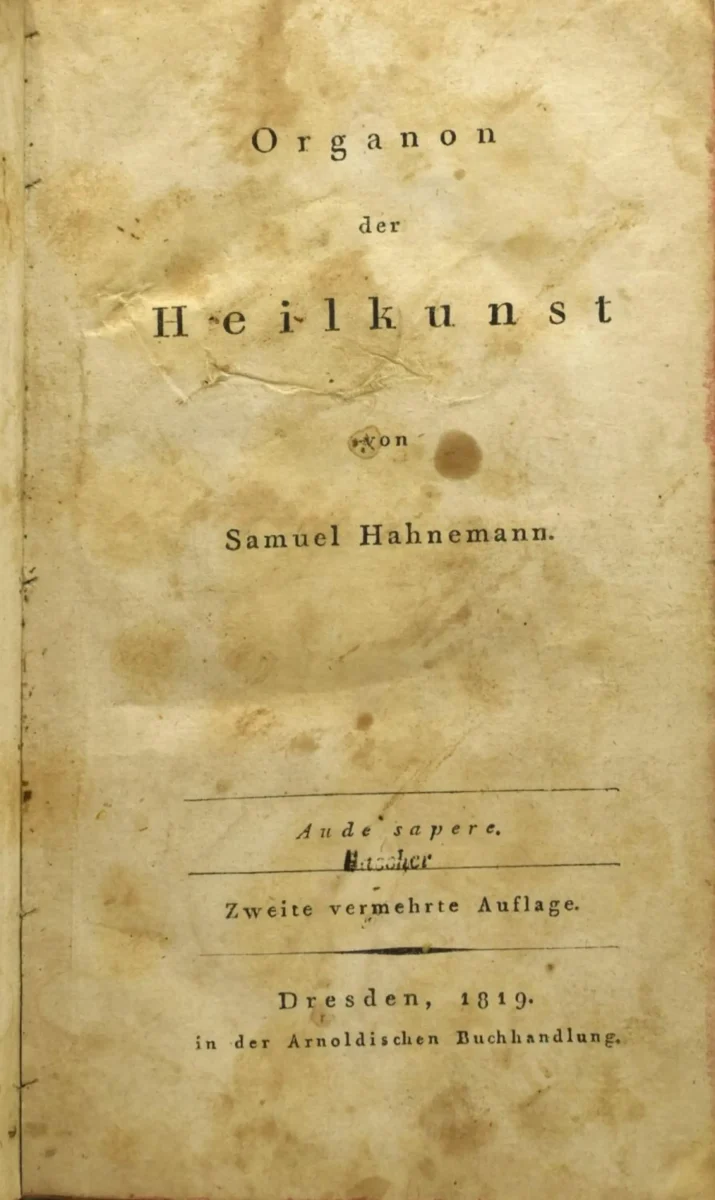

Cover of the first edition of Organon der rationellen Heilkunde (Dresden, 1819), by Dr. Samuel Hahnemann.

Source: public domain

Radetzky – General and Homeopathic Patient

Within this historical picture emerges a lesser-known but well-documented chapter of Radetzky’s life. According to homeopathic sources, around 1841, during his stay in Milan, General Radetzky suffered from a severe disease of the right orbital cavity - a progressive tumorous growth with pronounced exophthalmos and loss of vision. When the conventional medical methods of the time had exhausted their possibilitiesand a medical council assessed that further treatment was futile, prominent representatives of contemporary academic medicine withdrew from the case, among them Friedrich von Jaeger from Vienna’s Josephinum and Francesco Flarer from Pavia.

Equestrian monument of Josef Wenzel Radetzky von Radetz, 19th-century.

Image: Adobe Stock (licensed)

At that point Josef Radetzky chose a different path and accepted homeopathic treatment under the guidance of his chief physician Christoph Hartung, a student of Samuel Hahnemann. According to preserved reports in the homeopathic literature of the time, after several weeks of individualized homeopathic therapy there was a gradual, and then complete, regression of the tumorous growth and a restoration of ocular function. The historical weight of this case is further reinforced by a later document: in 1856, in Verona, Radetzky personally signed a statement confirming that the illness of 1841 had been cured exclusively by homeopathic treatment.

Music, Rhythm, and Healing

In 1848, Johann Strauss the Elder composed the Radetzky March as a dedication to General Radetzky and his military victory for Italian territory in the summer of 1848. That victory was the immediate impetus for Strauss’s composition, which he wrote very quickly following the news of Radetzky’s success, and which was premiered on August 31, 1848, in front of the city walls of Vienna. Today, the Radetzky March is a globally popular musical symbol of celebration and optimism. Beneath the triumphant surface of the march pulses an archetypal rhythm of order and repetition—a response of human consciousness to the chaos of change. The conquering edge dulls over time, but the rhythm remains , outliving empires.

Golden monument to Johann Strauss II, composer, Stadtpark Johann Strauss.

Image: Adobe Stock (licensed)

A Return to Rhythm

In the end, the journey that connects cities, history, music, and the body returns to the same source - the rhythm of life. In this understanding of rhythm, I recognize the shaping of my own homeopathic vocation, in which medicine once again encounters its original purpose: care for the whole human being. In the balance of body, consciousness, and spirit, matter and consciousness reveal themselves as perfect, eternal partners, who have never ceased to pulse in their unbroken, natural dance.

Lago di Como - from my personal archive

📜 Historical Note

The account of Radetzky’s treatment is based on 19th-century homeopathic medical literature and must be considered within the context of the diagnostic and therapeutic limitations of that era, particularly in the field of ophthalmology and the treatment of orbital pathological formations. Within this historical framework, available sources consistently record a favorable outcome of homeopathic treatment at a time when leading representatives of contemporary conventional medicine had deemed the condition incurable. This case suggests that the limitations of generally accepted and available medical methods of the time opened space for therapeutic approaches outside the dominant paradigm, with the literature highlighting the clinical effects of homeopathic remedies that were already well known and systematically applied in medical practice.

Christoph Hartung (1779–1853),

Historical lithograph, 19th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Reports of the regression of the disease and recovery of ocular function gain additional weight from the fact that Josef Radetzky later confirmed the treatment outcome in writing, thereby securing this case a place in medical-historical literature as a particularly intriguing and frequently cited example from the formative period of modern homeopathy. The treatment was documented by his personal physician, homeopath Dr. Christoph Hartung, in a private publication published in Munich in 1843.

📚 Selected Literature and Sources

Diocletian. Encyclopaedia Britannica,

www.britannica.com/biography/Diocletian (accessed 14 January 2026)

Matijević Sokol, M. Christian's SalonKnjiževni krug, 2023.

Riall, L. The Italian Risorgimento: State, Society and National Unification. Routledge, 1994.

Hahnemann, S. Organon of Medicine6th ed.,

https://www.bjain.com/organon-of-medicine (accessed 14 January 2026)

Dinges, Martin. “World History of Homeopathy.” Homeopathy, Elsevier.

(Article not available in open access)

Bradford, Thomas Lindsley. The Life and Letters of Dr. Samuel Hahnemann. 1895,

https://homeoint.org/books4/bradford/ (accessed 14 January 2026)

Hartung, Christoph. Geschichte und Documente der Krankheit und Heilung Sr. Exc. des k. k. Feldmarschalles Grafen von Radetzky, auf homöopathischem Wege. C. Wolf, 1843.

“Christophe Hartung (1779–1853).” Hahnemann House,

www.hahnemannhouse.org/christophe-hartung-1779-1853/ Accessed 14 January 2026.

“Malignant Tumours of the Eye — History of the Cure of Field-Marshal Radetzky.” British Journal of Homoeopathy, vol. 1, 1843, p. 147.

https://books.google.com/books?id=rPAEAAAAQAAJ Accessed 17 January 2026.

“Christoph Hartung.” Wikipedia,

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christoph_Hartung Accessed 17 January 2026.

Dinges, Martin, editor. Weltgeschichte der Homöopathie: Länder, Schulen, Heilkundige. C. H. Beck, 1996.